At the major league level, a pitcher’s arm can be worth tens of millions of dollars. Players, teams and Major League Baseball itself all have a vested interest in reducing season- and potentially career-ending arm injuries. Yet, according to a 2024 report by the league, tears to the ulnar collateral ligament, or UCL, have never been higher. In that report, the unprecedented speeds of today’s pitches, and their jaw-dropping spin and movement, are directly correlated with injury risk — specifically, risk for needing UCL reconstruction, the surgery made famous in 1974 by the Dodgers star Tommy John.

At the major league level, a pitcher’s arm can be worth tens of millions of dollars. Players, teams and Major League Baseball itself all have a vested interest in reducing season- and potentially career-ending arm injuries. Yet, according to a 2024 report by the league, tears to the ulnar collateral ligament, or UCL, have never been higher. In that report, the unprecedented speeds of today’s pitches, and their jaw-dropping spin and movement, are directly correlated with injury risk — specifically, risk for needing UCL reconstruction, the surgery made famous in 1974 by the Dodgers star Tommy John.

John’s post-surgery success (he came back to win an additional 164 games and continued pitching through the 1989 season) showed that a condition once known as “dead arm” was no longer a career-ender. By 2015, roughly a quarter of MLB pitchers had a history of UCL reconstruction. In recent years, that number has hit 35 percent.

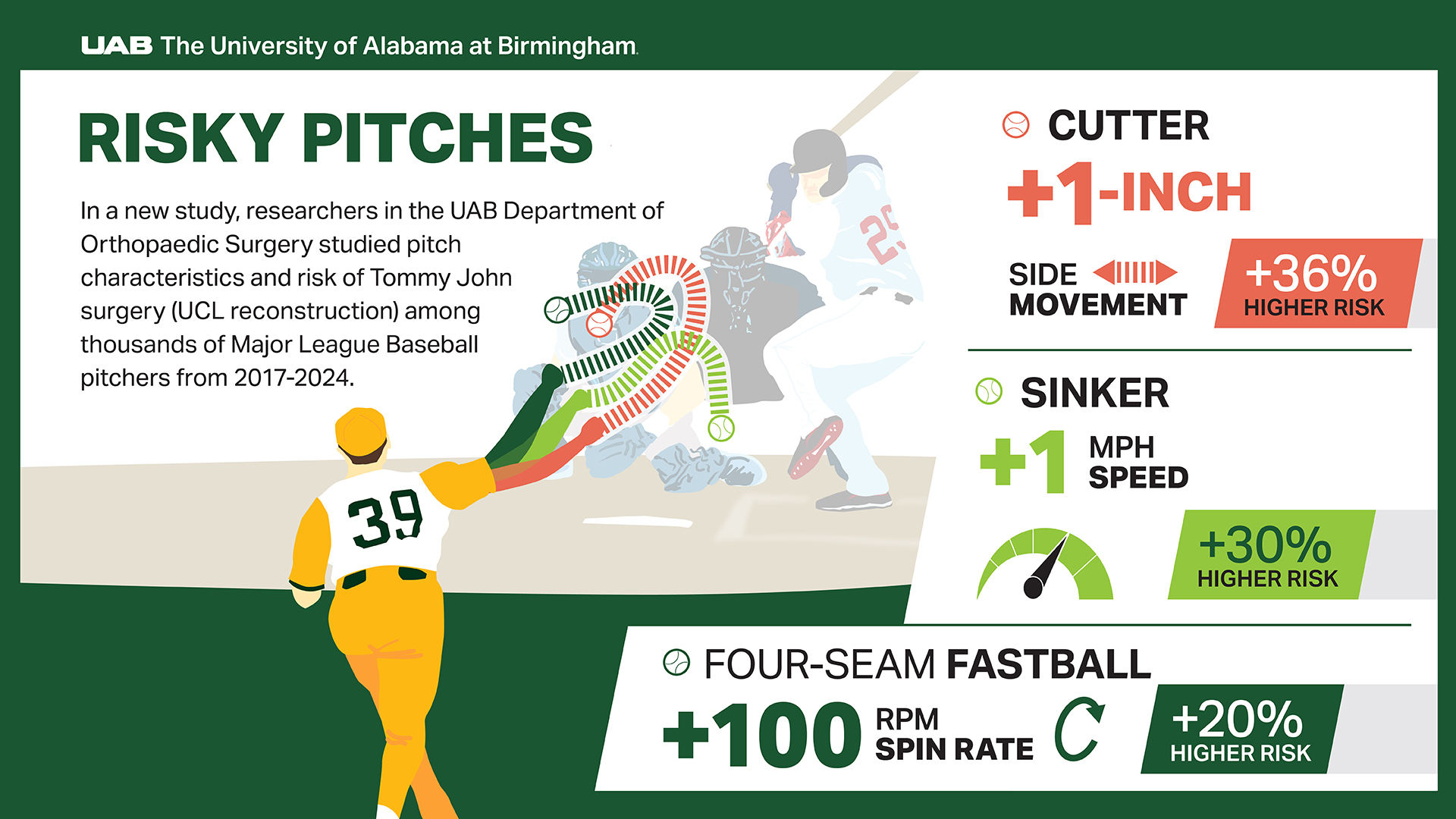

The link between speed, movement and UCL tears is well known. But a new study from researchers in the UAB Heersink School of Medicine's Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, led by sports medicine orthopaedic surgeon Amit Momaya, M.D., adds a twist. Using data from MLB’s vast Baseball Savant database, the UAB team compared the stats of pitchers who underwent UCL reconstruction between 2017 and 2024 to the thousands of pitchers who did not have Tommy John surgery over those seasons. Their goal was to identify any differences between pitchers who ended up needing surgery and those who did not.

Story continues below graphic

The 132 pitchers in the study who underwent UCLR during the 2017–2024 time frame did in fact have some distinguishing characteristics from the 6,001 league-average pitchers in those seasons who did not need UCLR. These included:

- greater average velocities for six specific pitches:

- four-seam fastballs

- sinkers

- cutters

- sliders

- changeups and

- curveballs;

- higher spin rates on their four-seam fastballs and changeups; and

- reduced glove-side horizontal movement.

“Although the association between increased valgus stress on the elbow and increased workloads with UCLR has long been established, the detailed analysis of pitch characteristics and their association with UCL injury has not been described,” Momaya and his co-authors wrote. (Valgus stress is the force that pushes the elbow joint in a direction where the forearm angles away from the body’s midline. The UCL’s job is to resist valgus stress at the elbow.) Their paper, “Increased Pitch-Specific Velocity, Spin Rate, and Horizontal Movement Lead to Increased Odds of Undergoing Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction in Professional Baseball Pitchers Using Baseball Savant Data,” was published in the journal Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopy and Related Surgery on July 28, 2025.

Watch out for the sinker

Amit Momaya, M.D., chief of Sports Medicine in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the UAB Heersink School of Medicine“The most important finding of this study is that pitchers who throw pitches with increased velocity, spin and movement are more likely to undergo UCL reconstruction when compared with healthy league averages,” Momaya explained.

Amit Momaya, M.D., chief of Sports Medicine in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the UAB Heersink School of Medicine“The most important finding of this study is that pitchers who throw pitches with increased velocity, spin and movement are more likely to undergo UCL reconstruction when compared with healthy league averages,” Momaya explained.

Was there a single pitch that stood out as particularly risky to throw harder? There was: the sinker (also known as the two-seam fastball). A 1-mile-per-hour increase in average sinker velocity resulted in a 30 percent increase in the odds of requiring UCLR.

The authors had hypothesized that curveball velocity would have the largest effect on UCL reconstruction risk. But throwing a curveball 1 mile per hour over league average increased odds of requiring UCLR only by a relatively small 11.1 percent.

Spin rate also was linked to injury risk for some pitches. Pitchers who threw a four-seam fastball with an average spin rate of 100 revolutions per minute above league average had a 20 percent increase in odds of undergoing UCLR.

Pitch movement was associated with injury risk as well. Increased arm-side movement of cutters had the most predictable link with injury risk: a 1-inch increase in arm-side movement above league average brought a 36 percent increase in odds of undergoing UCLR. (Changeups with 1 inch more of arm side movement than the league average changeup had a 9 percent increase in requiring UCLR.)

Previous research has already established that increased fastball velocity is a risk factor for UCL injury. But Momaya’s study found that increased velocity across several pitches — not only fastball variants such as the sinker and cutter, but also changeups, sliders and curveballs — was also a risk factor of injury.

“Given the financial implications, time to return to sport and competitive outcomes after UCLR, managers and team personnel should consider our findings when evaluating pitchers,” the authors wrote. “These findings are relevant clinically as pitchers are under constant pressure to push their bodies to extreme physical limits, chasing velocity throughout their entire pitch arsenal in order to succeed across all levels of competition.”

Young arms in trouble

Constant pressure? Sounds like today’s youth baseball culture, which has piled travel ball and nonstop tournament play — in every season but winter — on top of the school and local league teams that kids once played for in the spring and summer only.

And, indeed, Momaya has seen UCL surgery rates rising among young athletes in his practice. “We are definitely seeing more,” said Momaya, chief of UAB Sports and Exercise Medicine. “I counsel players and their parents based on some of the data comparable to this paper: the relationship between pitch velocity and the risk of UCL tears and the need for appropriate rest.”

In the words of the MLB report, “Though the data for amateur baseball isn’t as comprehensive as it is at the MLB level, the data reported by organizations like the American Sports Medicine Institute suggests that pitching injuries are growing more frequent and severe at the youth and high school level.”

Between 2019 and 2023, the report adds, youth and high school pitchers made up about half of overall UCL surgeries at one leading sports medicine center.

Warning signs and recovery times

Tommy John threw the pitch that tore his UCL in a July 1974 game against the Montreal Expos. It felt, he said later, as though he had “thrown his arm off his body.”

Today, the sensation that precedes Tommy John surgery is most often described as a pop. Sometimes, players and their parents will come to see Momaya because of a specific incident. In other instances, they have recurring pain in the elbow.

“The warning signs are a decreased velocity in pitching and starting to have medial elbow pain now and then,” Momaya said.

If a patient needs surgery, newer techniques are now available, Momaya said. “We used to always do reconstructions — just put a new rope in there,” he said. “Now we are doing more repairs, where we suture the ligament back together and augment with a biobrace or internal brace. That is what you are seeing across the nation.”

Recovery times vary widely, Momaya says. “It’s really dependent on skill level,” he noted. “In MLB, you see players coming back at one year, but it’s not a very great rate of success when they do that. Sometimes it takes a year and a half to two years to make it back to their former level.”

For high schoolers, the recovery rate is higher and faster, because “they are younger and healthier and the UCL does not have nearly as much wear buildup,” Momaya said. “Most high school kids can make it back, although a factor in there is that the level of competition on a high school team is not nearly as high as the level that a major league player needs to reach to compete again.”

Preventing UCL tears: Form, rest and variety

Despite the positive outcomes, surgery is still surgery, Momaya said: “You would be much better off avoiding a tear in the first place.”

Pitchers everywhere, from little leaguers to major leaguers, want to throw with power. Still, too many “pitchers don’t realize the importance of the core,” Momaya said. “Your arm is the whip that follows you; the body should generate power.” Exercises to build up core strength are a key to safely increasing velocity, he says.

The elaborate warmup and exercise routines used by star pitchers tend to filter down to young players; but proper form, taught by a knowledgeable coach, is the critical factor, Momaya said: “The message is getting out that power comes from the core rather than arm strength alone.” He has seen a number of athletes come in with arm injuries caused by improper form while using training devices — throwing with weighted balls, for instance. “Your technique and form are the most important,” Momaya said.

Recovery means rest

When he talks with patients, “I also ask how much they are throwing and whether they are playing for multiple teams,” Momaya said. “Often, they are playing school and rec and travel ball, all at the same time.”

With players on multiple teams, even when they are in leagues where pitch counts are monitored, “it really gets down to the parents” to keep up with their kids’ overall pitching load, Momaya said. He points parents to the published recommendations from Major League Baseball and national sports medicine societies. For kids ages 11–12, for example, the daily maximum pitch count should be 85 pitches, with anything more than 20 pitches triggering a day of rest, two days’ rest for 36–50 pitches, three days’ rest for 51–65 pitches and four days’ rest for 66-plus pitches.

The benefits of diversifying

Momaya, who himself pitched in high school, identifies with the pressures that kids, and parents, face. “I would play in two or three games in a tournament and throw 200 pitches in a day,” Momaya said. Today, baseball has become an almost year-round sport. “So many kids today are not only playing on multiple teams, but it’s almost all year long: summer, fall and spring. That doesn’t give you very much time to rest.”

In addition to a few days in between pitching outings, the UCL benefits from extended periods of rest, although that exact time frame is still a matter for research, Momaya says. “I encourage these athletes to do multiple sports,” he said. The overhead throwing motion of a baseball pitch is what brings the UCL wear; that motion is not seen in many other sports, Momaya says. “You can’t stop kids from wanting to get out and play,” he added, “but giving that elbow a rest makes a big difference.”

--

In addition to Momaya, authors of “Increased Pitch-Specific Velocity, Spin Rate, and Horizontal Movement Lead to Increased Odds of Undergoing Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction in Professional Baseball Pitchers Using Baseball Savant Data” are Maxwell Harrell, Clay Rahaman, Dev Dayal, Patrick Elliott, M.D., Caleb Berta, Eugene Brabston, M.D., Thomas Evely, D.O., Walter Smith, M.D., and Aaron Casp, M.D., all of the UAB Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, and Nathaniel Buchanan, a medical student at the Heersink School of Medicine.